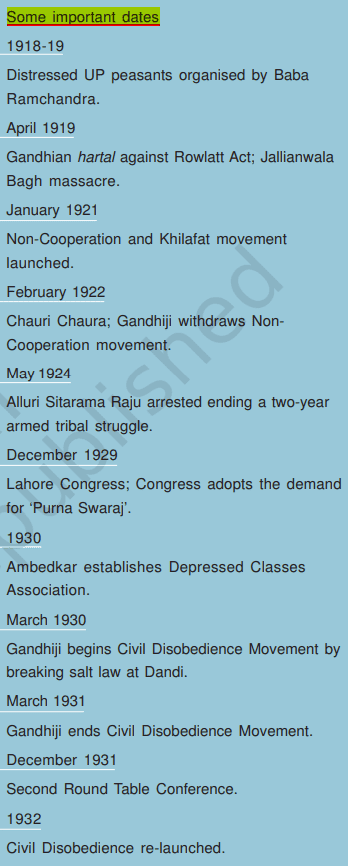

Welcome to our comprehensive notes on Class 10 History Chapter 2 Nationalism in India! This topic holds great significance in the CBSE Class 10 Board Exam as its weightage is 08 marks. Nationalism played a pivotal role in shaping the political landscape of India during the early 20th century, and it continues to influence our society today. In this guide, we will delve into the key concepts, events, and personalities that contributed to the growth of nationalism in India. From the effects of The First World War, Khilafat, and the Non-Cooperation to the sense of collective belonging, we will explore the struggles, sacrifices, and triumphs of Indian nationalists who fought tirelessly for the freedom we enjoy today. Through concise explanations, engaging examples, and helpful study tips, this guide aims to equip class 10 students with a solid understanding of the topic.

| Subject | Social Science (History) |

| Class | 10 |

| Board | CBSE |

| Chapter No. | 2 |

| Chapter Name | Nationalism in India |

| Type | Notes |

| Session | 2024-25 |

| Weightage | 8 marks |

"The best way to get started is to quit talking and begin doing."

- Walt Disney

Nationalism in India Class 10 Notes

Table of Contents

The First World War, Khilafat, and Non-Cooperation

Impact of WWI on India

- Economic Strain: The war led to a massive increase in military spending by the British government in India. This was financed by raising taxes (customs duties and income tax) and war loans, putting a burden on the Indian population.

- Inflation and Hardship: Prices of goods doubled between 1913 and 1918, causing significant hardship for ordinary people.

- Forced Recruitment: Villages were forced to provide soldiers for the war effort, leading to anger and resentment.

- Famines and Epidemic: Crop failures in 1918-19 and 1920-21 resulted in food shortages, worsened by a deadly influenza epidemic. Millions died (estimated at 12-13 million) due to these combined factors.

The Idea of Satyagraha

- Developed by Gandhi: The concept of Satyagraha originated in South Africa where Gandhi successfully used it against racial discrimination.

- Emphasis on Truth: Satyagraha emphasizes the power of truth and the pursuit of justice. It argues that a righteous cause doesn't need violence to succeed.

- Non-Violent Resistance: Satyagraha advocates for non-violent resistance against oppression.

- Appealing to Conscience: The idea is to win over the oppressor through peaceful means, appealing to their sense of right and wrong. Persuasion, not force, is key.

- Ultimate Triumph of Truth: Satyagraha believes that truth will eventually prevail through persistent non-violent struggle.

Examples of Satyagraha Movement: After arriving in India, Mahatma Gandhi successfully organized satyagraha movements in various places.

- Champaran (1917): Supporting peasants against an oppressive plantation system.

- Kheda (1917): Backing peasants demanding relaxed revenue collection due to crop failure and an epidemic.

- Ahmedabad (1918): Organizing a movement for better working conditions for cotton mill workers.

The Rowlatt Act

Gandhiji, in 1919, decided to launch a nationwide satyagraha against the proposed Rowlatt Act of 1919.

Provisions of the Rowlatt Act were:

- It gave the government the power to repress any political activity or demonstration.

- It allowed the detention of political prisoners without trial for two years.

- The British government could arrest anyone and search any place without a warrant.

The Rowlatt Act was opposed by Indians in the following ways:

- A non-violent civil disobedience against the unjust law began.

- Rallies were organized in various cities.

- Workers went on strike in railway workshops.

- Shops were closed down in protest.

Jallianwalla Bagh incident:

- On 13 April, the Jallianwalla Bagh incident took place.

- On that day a crowd of villagers who had come to Amritsar to attend a fair gathered in the enclosed ground of Jallianwalla Bagh.

- Being from outside the city, they were unaware of the martial law that had been imposed.

- Dyer entered the area, blocked the exit points, and opened fire on the crowd, killing hundreds.

- His object, as he declared later, was to ‘produce a moral effect’, to create in the minds of satyagrahis a feeling of terror and awe.

The reasons for starting the Khilafat Movement

- With the defeat of Ottoman Turkey in the First World War, there were rumors that a harsh peace treaty was going to be imposed on the Ottoman emperor (the Khalifa).

- Muslims all over the world began to support the temporal powers of the Khalifa. In India, too Khilafat Committee was formed under the leadership of Muhammad Ali and Shaukat Ali.

- At the Calcutta session of the Congress in September 1920 he convinced other leaders of the need to start a non-cooperation movement in support of Khilafat and Swaraj.

Why Non-cooperation?

In his famous book Hind Swaraj (1909) Mahatma Gandhi declared that British rule was established in India with the cooperation of Indians, and had survived only because of this cooperation. If Indians refused to cooperate, British rule in India would collapse within a year, and Swaraj would come.

Non-cooperation movement:

At the Congress session at Nagpur in December 1920, a compromise was worked out and the Non-Cooperation program was adopted.

It should begin with the surrender of titles that the government awarded, and a boycott of civil services, army, police, courts and legislative councils, schools, and foreign goods.

Non-Cooperation-Khilafat Movement began in January 1921. All of them responded to the call of Swaraj, but the term meant different things to different people.

Differing Strands within the Movement

The Movement in the Towns

- The movement started with middle-class participation in the cities.

- Thousands of students left government-controlled schools and colleges

- Headmasters and teachers resigned.

- Lawyers gave up their legal practices.

- The council elections were boycotted in most provinces except Madras.

- Foreign goods were boycotted, liquor shops picketed, and foreign cloth burnt in huge bonfires.

- Merchants and traders refused to trade in foreign goods.

- Production of Indian textile mills and handlooms went up.

The Non-Cooperation Movement in the cities gradually slowed down because:

- Khadi cloth was more expensive than mass-produced mill cloth and poor people could not afford to buy it.

- The boycott of British institutions failed because Indian institutions could not be set up in place of the British ones.

- Students and teachers began trickling back to government schools.

- The lawyers too joined back work in government courts.

Rebellion in the Countryside

Awadh Peasants:

- Peasants of Awadh were led by Baba Ramchandra, a sanyasi. The movement was against talukdars and landlords. The landlords and talukdars demanded exorbitantly high rents and other cesses.

- Peasants had to do beggar (unpaid work) and work at landlords’ farms without any payment.

- As tenants they had no security of tenure, being regularly evicted.

- The peasant movement demanded a reduction of revenue, the abolition of beggar, and a social boycott of oppressive landlords.

- In many places, nai-dhobi bandhs were organized by panchayats to deprive landlords of the services of barbers and watermen.

- Oudh Kisan Sabha was set up and headed by Jawaharlal Nehru, Baba Ramchandra, and a few others.

- In 1921, the houses of talukdars and merchants were attacked, bazaars were looted and grain hoards were taken over.

Tribal Peasants:

The causes that led the tribals to revolt in the Gudem Hills of Andhra Pradesh were:

- The colonial government had closed large forest areas preventing people from entering the forests to graze their cattle, or to collect fuelwood and fruits. This enraged the hill people.

- Not only were their livelihoods affected but they felt that their traditional rights were being denied.

- When the government began forcing them to contribute beggar (work without payment) for road building, the hill people revolted.

Role of Alluri Sitaram Raju:

- Alluri Sitaram Raju was a tribal leader in the Gudem hills of Andhra Pradesh.

- He started a militant guerrilla movement in the Gudem Hills of Andhra Pradesh.

- The tribal people were against colonial policies. Their livelihood was affected and their traditional rights were denied.

- Their leader Alluri Sitaram Raju was inspired by Gandhiji’s Non-Cooperation movement and persuaded people to wear khadi and give up drinking.

- He claimed that he had a variety of special powers like making astrological predictions, healing people, and surviving bullet shots.

- He persuaded people to wear khadi and give up drinking.

- But at the same time, he asserted that India could be liberated only by the use of force, not non-violence.

Swaraj in the Plantations

Meaning of Swaraj for Plantation Workers: For plantation workers in Assam, Swaraj meant the right to move freely in and out of the confined space in which they were enclosed, and it meant retaining a link with the village from which they had come.

- Under the Inland Emigration Act of 1859, plantation workers were not permitted to leave the tea gardens without permission, and in fact, they were rarely given such permission.

- When they heard of the Non-Cooperation movement, thousands of workers defied the authorities, left the plantations, and headed home.

- They believed that Gandhi Raj was coming, and everyone would be given land in their own villages.

- They, however, never reached their destination. Stranded on the way by a railway and steamer strike, they were caught by the police and brutally beaten up.

At Chauri Chaura in Gorakhpur, a peaceful demonstration in a bazaar turned into a violent clash with the police. Hearing of the incident, Mahatma Gandhi called a halt to the Non-Cooperation Movement.

Towards Civil Disobedience

Gandhiji decided to withdraw the Non-Cooperation Movement in February 1922 because:

- The movement was turning violent in many places.

- He felt that the satyagrahis needed to be properly trained before they would be ready for mass struggles.

Two factors again shaped Indian politics in the late 1920s.

- The first was the effect of the worldwide economic depression. Agricultural prices began to fall from 1926 and collapsed after 1930. As the demand for agricultural goods fell and exports declined, peasants found it difficult to sell their harvests and pay their revenue. By 1930, the countryside was in turmoil.

- Simon Commission: Set up in response to the nationalist movement, the commission was to look into the functioning of the constitutional system in India and suggest changes. The problem was that the commission did not have a single Indian member. They were all British.

In an effort to win them over, the viceroy, Lord Irwin, announced in October 1929, a vague offer of ‘dominion status’ for India in an unspecified future, and a Round Table Conference to discuss a future constitution.

In December 1929, under the presidency of Jawaharlal Nehru, the Lahore Congress formalized the demand for ‘Purna Swaraj’ or full independence for India. It was declared that 26 January 1930, would be celebrated as Independence Day when people were to take a pledge to struggle for complete independence.

Lala Lajpat Rai was assaulted by the British police during a peaceful demonstration against the Simon Commission. He succumbed to injuries that were inflicted on him during the demonstration.

The Salt March and the Civil Disobedience Movement

- On 31 January 1930, Gandhiji sent a letter to Viceroy Irwin stating 11 demands, the most stirring of which was the demand to abolish the salt tax.

- Salt was one of the most essential items of food. Tax on salt and the government monopoly over its production, Gandhi declared, revealed the most oppressive face of British rule.

- Irwin was unwilling to negotiate and so, Mahatma Gandhi started his famous 240 miles long Salt March accompanied by 78 of his trusted volunteers.

- The march was over 240 miles, from Gandhiji’s ashram in Sabarmati to the Gujarati coastal town of Dandi.

- On 6 April he reached Dandi, and ceremonially violated the law, manufacturing salt by boiling seawater.

Features of the Civil Disobedience Movement:

- The movement started with Salt March.

- Thousands broke salt law.

- Foreign clothes were boycotted.

- Liquor shops were picketed.

- Peasants refused to pay taxes.

People were now asked not only to refuse cooperation with the British but also to break colonial laws.

Gandhiji relaunched the Civil Disobedience Movement after the Second Round Table Conference because:

- When Mahatma Gandhiji went to the Round Table Conference in December 1931, he returned disappointed as the negotiations were broken down.

- Back in India, he discovered that the government had begun a new cycle of repression.

- Ghaffar Khan and Jawaharlal Nehru were both in jail

- The Congress had been declared illegal.

- A series of measures had been imposed to prevent meetings, demonstrations, and boycotts.

The reasons for the participation of various social classes and groups in the Civil Disobedience Movement are as follows:

- Rich peasants: Rich peasant communities like the Patidars of Gujarat & the Jats of Uttar Pradesh joined the movement because being producers of commercial crops they were hard hit by the trade depression and falling prices. The refusal of the government to reduce the revenue demand made them fight against high revenues.

- Poor peasants: Joined the movement because they found it difficult to pay rent. They wanted the unpaid rent to the landlord to be remitted.

- Business class: They reacted against colonial policies that restricted activities because they were keen on expanding their business and for this, they wanted protection against imports of foreign goods. They thought that Swaraj would cancel colonial restrictions and that trade would flourish without restrictions. They also wanted protection against the rupee-sterling foreign exchange ratio. They formed the Indian Industrial and Commercial Congress in 1920 and the Federation of the Indian Chamber of Commerce and Industries (FICCI) in 1927.

- Industrial working class: They did not participate in large numbers except in the Nagpur region. Some workers did participate, selectively adopting some of the Gandhian programs, like boycotts of foreign goods, as a part of their own movements against low wages and poor working conditions.

- Women: There was large-scale participation of women in the movement. They participated in protest marches, manufactured salt, and picketed foreign cloth and liquor shops. Many went to jail.

- Merchants and Industrialists:

- Indian merchants and industrialists were keen on expanding their businesses and reacted against colonial policies that restricted business activities.

- They wanted protection against imports of foreign goods, and a rupee-sterling foreign exchange ratio that would discourage imports.

- To organize business interests, they formed the Indian Industrial and Commercial Congress in 1920 and the Federation of the Indian Chamber of Commerce and Industries (FICCI) in 1927.

- Led by prominent industrialists like Purshottamdas Thakurdas and G. D. Birla, the industrialists attacked colonial control over the Indian economy and supported the Civil Disobedience Movement.

- They gave financial assistance and refused to buy or sell imported goods.

- Most businessmen wanted to flourish in trade without constraints.

The limitations of the Civil Disobedience Movement were:

- Half-hearted participation of untouchables. Congress had ignored the Dalits for fear of offending the Sanatanis, the conservative high-caste Hindus.

- After the decline of the Non-Cooperation-Khilafat movement, a large section of Muslims felt alienated from Congress.

- As relations between Hindus and Muslims worsened, each community organized religious processions with militant fervor. This provoked Hindu-Muslim communal clashes and riots in various cities.

Untouchability:

- Mahatma Gandhi was against untouchability. He declared that Swaraj would not come for a hundred years if untouchability was not eliminated. He called the ‘Untouchables’ harijan or the children of God.

- He organized satyagraha to secure their entry into temples, and access to the public wells, tanks, roads, and schools.

- He himself cleaned toilets to dignify the work of the sweepers.

- He persuaded the upper caste to change their heart and give up ‘the sin of untouchability’.

Poona Pact of September 1932:

The Poona Pact of September 1932 gave the Depressed Classes (Schedule Castes) reserved seats in provincial and central legislative councils, but they were to be voted in by the general electorate.

Some of the Muslim political organizations in India were lukewarm in their response to the Civil Disobedience Movement:

- Large sections of Muslims were lukewarm in their response to the Civil Disobedience movement.

- The decline of Khilafat and Non-Cooperation movements led to the alienation of Muslims from Congress.

- From the mid-1920s, the Congress was seen to be visibly associated with Hindu nationalist groups like the Hindu Mahasabha.

- Relations between Hindus and Muslims worsened and communal riots took place.

- The Muslim League gained prominence with its claim of representing Muslims and demanding a separate electorate for them.

The Sense of Collective Belonging

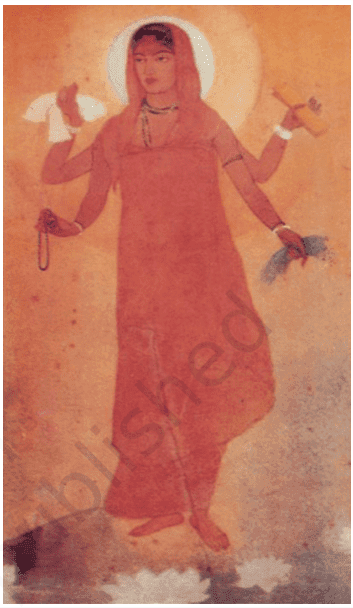

- The identity of the nation is most often symbolized by the image of Bharat Mata.

- Bankim Chandra Chattopadhyay wrote ‘Vande Mataram’ as a hymn to the motherland.

- Moved by the Swadeshi movement, Abanindranath Tagore painted Bharat Mata and portrayed it as an ascetic figure. She is shown as calm, composed, divine, and spiritual.

- Ideas of nationalism also developed through a movement to revive Indian folklore.

- Icons and symbols in unifying people and inspire in them a feeling of nationalism.

- During the Swadeshi movement in Bengal, a tricolor flag (red, green, and yellow) was designed.

- Reinterpretation of history to instill a sense of pride in the nation.

Abanindranath Tagore painted the above image of Bharat Mata.

In this painting Bharat Mata is portrayed as an ascetic figure; she is calm, composed, divine, and spiritual.

Reinterpretation of history created a sense of collective belongingness among the different communities of India:

- By the end of the nineteenth century many Indians began feeling that to instill a sense of pride in the nation, Indian history had to be thought about differently.

- The British saw Indians as backward and primitive, incapable of governing themselves.

- In response, Indians began looking into the past to discover India’s great achievements. They wrote about the glorious developments in ancient times when art and architecture, science and mathematics, religion and culture, law and philosophy, and crafts and trade flourished.

- These nationalist histories urged the readers to take pride in India’s great achievements in the past and struggle to change the miserable conditions of life under British rule.

Download Nationalism in India Class 10 NCERT Underlined PDF

Hope you liked these Notes on Class 10 History Chapter 2 Nationalism in India. Please share this with your friends and do comment if you have any doubts/suggestions to share.

Sir please upload rest of the chapter notes

Yes as soon as possible

Sir please upload Print culture

Sir sst me likhna nahi aa question grammar mistak hota hai please solve this problem

Sir the website is best but there are some non covered topics in many chapters please add it asap

kya aap st soldier wali ho?

Thankyou sir

realy very useful notes thanks a lot

sir. Is this enough for board preparation

Yes along with provided important questions and answers.